YuYu interview Alan Pate

|

| —— Can you tell me a little about this ningyo exhibition “Ningyo: The Art of the Japanese Doll” that you are guest-curator of here at the Mingei International Museum in Balboa Park? This particular grouping comes from 7 different lenders across the US and I would say this is the best, most comprehensive, display ever attempted outside of Japan. I would push the point further saying, that, in terms of breadth, it would push anything that’s ever been done in Japan as well. It focuses on six categories of ningyo: gosho-ningyo (palace dolls), hina-ningyo (Girl’s Day dolls), musha-ningyo (Boy’s Day dolls), isho-ningyo (dolls of fashion and popular culture), karakuri-ningyo (theater dolls, some of which are mechanical) and dolls relating to health. I’m not saying that there aren’t better examples in Japan, but in terms of breadth, this would give most any Japanese exhibition a run for its money. Every country in the world has a doll culture, every one; it’s just instinctual. Ningyo by origin can be traced back to prehistory of Japan. Basically, in 3000 or 4000 BC, the Jomon period, they were using clay figurines for fertility rights. And you can trace, from that moment on, historically, archeologically and culturally that ningyo have played an essential role in any number of cultural rights and practices, including their richly textured layered ceremonies and have been infused into the Japanese psyche to a degree. Consequently, ningyo resonate with Japanese on a far deeper level and so the way they view them is different. Antique ningyo that have passed through people’s hands and passed through their families, even today in contemporary Japan and with the most educated person, they are still going to feel that there is a residue, a lingering essence from these other families that they don’t want to bring into their home. It is that very reason it is possible to put together a collection of this magnitude outside of Japan, as opposed to some other art forms that are far more difficult to pry away. —— So would you say that our concept of the word doll doesn’t encompass the depth that ningyo does? Oh, very easily you can say that. The word doll, while it is the translation, is not true to the spirit; it’s not true to the essence; it’s not true to the expansiveness of the term ningyo in Japanese. We don’t have a term that truly describes it and doll falls far short. It doesn’t exist in English because a doll is a plaything; a doll is something lesser. It’s a doll with a small “d” as opposed to something with more weight, something legitimate. One of the thing first things we need to do is explain that these by and large were not made for children; the vast majority of what you see weren’t meant to be handled by children-they were display dolls or they were used for very specific functions that fell very much into an adult purview. —— You mentioned that as long as we can remember this art form has been around, when did the art form take the shape that we see here at the exhibit? The Edo period. It’s totally an Edo art form when there was a confluence of peace, stability, and rapidly rising fortunes. Society was awash with money and they could focus on things like ningyo to elevate them to forms that they never achieved before. If you go back to the Muramachi period and the Momoyama period you’ll see paintings of noblemen or noble children with their ningyo, but in comparison they are very rudimentary. During the Edo period, very quickly, these rudimental figures began to evolve in to something totally other and I think to my mind they reached their apex during the Edo period. They’ve been in decline ever since in terms of the value system that I place on them. It has to do with cultural resonance issues, which I guess a contemporary ningyo artist would be very offended by that comment. While modern craftsmen are bringing in a great deal of artistry and care, and I respect that and honor that, but I think that there is a disconnect between what they are doing and what was once done. I think once you started introducing western technology, the aniline dyes and manufacturing processes, there was a shift and it’s different. The antique dolls reflect on a different era, from style to equipment and materials. They have aged, mellowed and reacted to time and that gives them a quality that I truly appreciate. It gives them a subtle yet unduplicable character. —— Speaking of materials, what are ningyo generally made from?

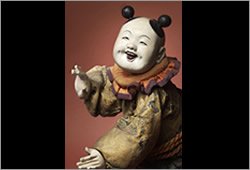

Ningyo with mechanical features, such as this gosho-ningyo, have moving arms that allow raising its mask. Photo by Lynton Gardiner

Well, basically, the 3 materials that define many of the ningyo would be wood, silk and gofun. Wood comes into play as the base form, from which these things are carved, sculpted and created. The silk is used to ornament that basic body and the silks are your brocades, compound weaves, your gauze weaves, practically every aspect of textile technology, and the Japanese are unsurpassed in their textile technologies. Finally, there is the gofun, or pulverized oyster shell and animal glue composite, which was applied on the surface and gives the ningyo their opalescent porcelain sheen. Gofun, although introduced from China and further west along the silk-road, we suspect originated in Persia. It was applied by brush on the base material and then burnished layer upon layer, quite similar to a lacquer technology. The animal glue composite gave it a certain plasticity, so it was also used for minor molding. Some of the faces are not fully wood sculpted, rather articulated with the gofun itself. It really creates something otherworldly and it is the most distinctive characteristic of the Japanese dolls-that shining white face. Gofun, however, is both the boon and bane of ningyo in that it creates a transcendent beauty, but it is also so fragile. You apply it over a wood core, but the wood itself is expansive and contractive, while the gofun is not. Under the right conditions gofun can last perfectly for hundreds and hundreds of years, but give it too much heat or humidity and the wood will expand or contract and then you’ll get cracking-and if you apply water you will actually wipe the gofun away! A well known collector remembers when she was quite young and her father, also a ningyo collector, had brought home a gosho-ningyo that the family was just gaga over. It was absolutely amazing and worth roughly the equivalent of their home. Well, her younger brother saw that the family was very excited about all of this, but also saw that the doll was not quite clean; it was slightly soiled. So he decided to help out and clean it-by taking it into the ofuro with him! There he carefully and lovingly cleaned it and later proudly presented the now clean and gofun-less ningyo to the family. It is an intuitive thing for most people to want to clean them by wetting their finger or taking a moist rag to shine them right up. Well that will eat right through the gofun like nobody’s business! You just can’t treat it like porcelain; you can’t treat as anything but what it is. —— Is it true that some ningyo were thought to have powers or some spiritual purpose? As I mentioned, early forms from prehistory in Japan were used in rites and rituals that have continued arguably till today and there are still ceremonies in which dolls are ritually burned to engage in purification. In the exhibition we have examples, the red dolls, that were used specifically to protect children from measles. The red color was thought to attract and absorb the disease. They are very rare forms now, because once the hosogami, or demon, of small pox or measles entered the doll you wanted to get rid of it. You didn’t want to keep it around. Also, the two dolls at the entrance, the amagatsu and the hoko, were specifically talismanic dolls that were made at a child’s birth to protect the child from birth. For a male it stayed with him until he had his coming of age ceremony and then it was traditionally burned, but for the female it stayed with her for her entire life. In addition, there is the concept of yorishiro, or temporary lodging place, that ningyo fulfilled as a place of habitation for spirits various kinds. —— So Alan, what about your own personal interest in ningyo, how did it start and then turn into this quest? My personality is such that I like the unusual. I like the things that most people don’t know about-the road less traveled. So, when I find something that I don’t understand I like to ask questions and if the person I ask can’t answer them all the better. My first encounter with ningyo was in an antique shop in Seattle. My first partner in Seattle was a Japanese antique dealer and when we’d travel to Japan, he would be buying and I would be asking my questions. But no one really answered them or if they did it smacked of being rote. As I tried to dig deeper, I came to find that even they did not know! When people don’t know they tend to make up things, and dealers are notorious for doing this-they create back-stories for their pieces. They are great sales techniques, but they are not based in reality. And so it began. As my interest and knowledge grew, I developed a friendship with the editor of a magazine called “Daruma” and she asked me if I could write an article on ningyo, which I did. I had already been collecting my own notes and research, but this forced me to investigate ningyo in a more systematic way and communicate it. One article lead to another, first I did one on Boy’s Day and then another on hina-matsuri. At that point I realized that a book had to be written, then looking around I realized that would be me! And so I knew it was going to happen, it was just a matter as to what was going to be the catalyst. —— And so what was the catalyst?

Some ningyo transcend their wood, silk and gofun. If you listen closely̶you can almost hear this isho-ningyo laughing. Photo by Lynton Gardiner.

Deadlines. I’ve been researching ningyo for 10 years and probably would have continued researching this for another 10 years if Martha Longenecker hadn’t said, “Let’s do an exhibition. It’s got to have a book and we want it to start in June of 2005.” That really made me focus. I’m addicted to research and I’d still be out their doing it today…and actually I still am. This show here at the Mingei is actually the launch of the book. It is available here first before anywhere else. —— Was it difficult to pierce the veil of myth surrounding ningyo? In a word, yes. You have to listen to what’s said, look at the form itself, think about history and then look into the old documents. An invaluable resource for me have been the early early wood-block prints, before nishiki, when they were just black and white line drawings. They show ningyo in the house as a part of a festival, or in a shop and how they were displayed and you can go through and find woodblock prints from the 1600s and 1700s and begin to document when a particular form was introduced. That is because the wood-block print artists were the great documentarians of their day and that resource is still available to us today and accessible just by looking at them. For the last 4 or 5 years I’ve been traveling to Japan every other month, buying and doing research to ferret out more information, because so little has actually been published in English or in Japanese. I’ve had to go to as many different sources as possible to cobble together the story that I’ve been trying to tell. I’ve spoken with a number of curators that are very good at what they do and collectors who have a deep passion for ningyo and they have lots of stories and insights that are not written in books. I’m also going to archival sources. Part of the book deals with government regulations of ningyo during the Edo period, so I needed to track down the original furigake and get those interpreted. The more I got into it, the more passionate I became. My level of enthusiasm is far greater than when I started. I knew there was more to it, but I didn’t really know what and as I found out it became all the more intriguing. It just screams to be let out, especially for lovers of Japanese art or Japanese culture-they need to know this. Piece by piece they help to crack open the shell of Edo popular culture, which is quite a fascinating world. —— So the dolls themselves reflect on the culture in a way that couldn’t be voiced in other ways? Right. It’s curious that you use the word reflection, because in Japanese the expression “The Great Mirror” has been used since Heian period to show the power that art or a poem has to reflect back on culture. Originally, I was going to call my book, “The Great Mirror of Japanese Dolls,” so if you look at the insert it says, “mirroring Edo culture”. This concept is something that I always held in my head-that ningyo are a lens through which I can dissect and explore an amazing period of Japanese cultural history. It is sociological; it’s cultural history; it’s physical history, textiles, trade, and politics. As I went deeper I realized that I could probably explore every conceivable topic in Japanese culture-talk about degrees of separation-through ningyo. All of these things that may not seem logically to be connected to dolls, but I can get there in one step. It’s amazing. —— I understand that you have one of the “friendship dolls” here, what is the story behind them?

This“Friendship Doll”, from 1927, was one of only 58 ever created as gifts from Japan to each of the 50 states and select museums. Photo by Lynton Gardiner.

Our friendship doll Miss Kanto-shu, or Miss Manchuria, is from 1927, way outside my date parameter, but in terms of importance it is unique in that only 58 were ever made and only 44 are known to be in existence. During the 1920s there was a growing anti-Asian sentiment and restrictive laws were enacted curtailing any number of civil rights. Responding to that and as an attempt to promote harmony and understanding between our countries, Reverend Sydney Gulick spearheaded a drive that saw US school children send some 12,739 “blue-eyed” dolls to Japanese school children. In return, from Japan came the 58 friendship dolls or ichimatsu-ningyo. Each state received one along with handful of major museums, with each doll being named after a major city, region or territory of Japan, so there are dolls like our Miss Man churia, and so on. They were well received and displayed until the war, during which time people naturally weren’t that keen on Japan, so they were all removed. The one on display here was found in a sort of flea market in New Jersey, far away from it’s original home in many respects. Fortunately, a collector recognized it and rescued it. —— So even such meaningful examples continue to be under appreciated. What is your hope for us and for ningyo?

Alan, alongside the exquisite bunraku-ningyo. Ningyo such as this were puppets, with moveable heads, hands, eyes and eyebrows

In many respects this is not only an overlooked form in the west - it’s an undervalued form in Japan too. Go to Kyoto or Tokyo, bastions of Japanese culture, and they allocate so few resources to ningyo. Very little is done in terms of exhibitions and in terms of research and documentation. I’ve thrown my book and this exhibition out there as a challenge-to other scholars, academics, researchers and the art community-and now they have to deal with it. I’m really curious to see what the Japanese experts have to say now that I’ve opened the debate. My sincere goal, and I think a realistic one, is to raise the knowledge and awareness of this particular art form. I have no illusions that it is going to become as popular as anime…it’ not likely! What I would like is for the word ningyo to become better understood and more widely recognized. I don’t think it will ever become a household word, but particularly on the institutional level, I would like to see each and every museum that has an Asian Art collection have respectable examples that they display periodically. Most museums don’t even have a ningyo collection and these are places that ought to know better. They should be more aware and have a greater respect for the form and a courage and understanding to introduce it to their public-that’s the mandate of a museum. The ultimate purpose of a museum is to educate and from education comes appreciation. Understanding breeds appreciation. I have a very strong belief that we are only temporary custodians of these marvelous pieces. They’ve already survived 300 years and I know that I can’t keep them long personally; I’m only holding them for a moment in what I hope will be a very long lifetime. (08-01-2005 issue, Interviewed by Terry Nicholas) |